Inside Barns-Graham’s Library

Margaux Beux-Pauly is an exchange student from the Ecole du Louvre, studying in Museum and Heritage Studies at the University of St Andrews. As part of her degree course, she has been cataloguing the library of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham.

An impressive number of writings

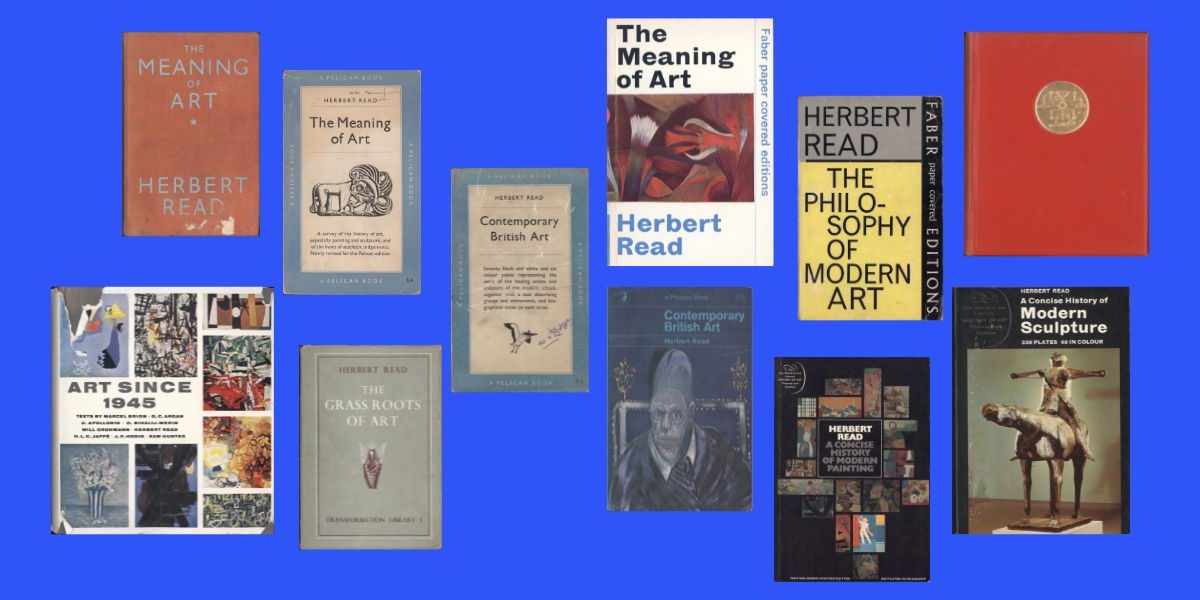

When I began cataloguing the books in the library of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, half of the books had already been catalogued, so I was catapulted into the heart of Barns-Graham’s books on art theory. Barns-Graham seemed to be interested in a wide variety of European modern art movements; from the French avant-garde to Russian and Native American art, with a predilection for British art. This suggestion of love and in-depth knowledge of British art is demonstrated by an impressive number of writings – some in multiple copies – by art critic and surrealist poet Herbert Read.

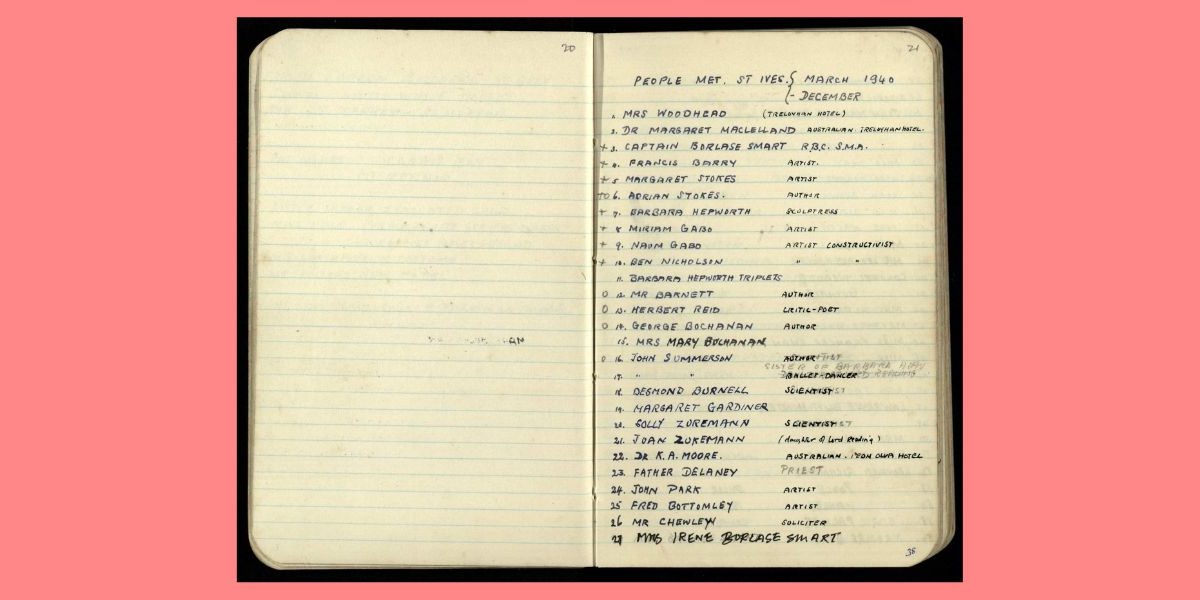

'People met in St Ives'. Extract from Barns-Graham's St Ives 1940-41 diary (WBG/4/1/5)

Herbert Read, ‘critic-poet’ as Barns-Graham described him in her diary from 1940 when she arrived in St Ives, was a renowned art historian, art critic, poet and philosopher who is best known for his exploration of the role of art in education. Barns-Graham’s library contains around twenty books written by or about Herbert Read. These include seven different copies of Contemporary British Art and four copies of The Meaning of Art. Some of these books also belonged to Barns-Graham’s Studio Manager Rowan James. Despite this, there can be no doubting Barns-Graham’s attraction to Herbert Read’s critical art theory.

A shelf in Barns-Graham's library

How did reading Herbert Read, and seeing him lecture, influence Barns-Graham’s artistic vision?

As Lynne Green explains in the prologue to her book W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life, there is no question in this article of reducing Barns-Graham’s thinking or output to the influence of one man (Green, 2011). The point here is simply to conjecture and observe how and if – after reading Read’s texts and spending time with him – Barns-Graham incorporated these art historical interpretations into elements of her artistic practice.

Barns-Graham was reading the writings of Herbert Read as far back as her early student days at the Edinburgh College of Art, where, as Lynne Green mentions, Barns-Graham discovered another world through her teachers, her fellow students, through reading “[…] and in illustrated lectures by key figures in the arts of the day – Herbert Read and John Summerson among them.” (Green, 2011)

Herbert Read was therefore an essential figure for Barns-Graham, dealing not only with his writings on modernism, but also with art in general, notably in The Meaning of Art, published in 1931. This book – of which there are four in the library – not only investigates the meaning of art, but also focuses on numerous modern and contemporary artists who greatly inspired Barns-Graham’s research, such as Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Hans Arp. Other artists mentioned include Henry Moore and Edvard Munch (King, 1990).

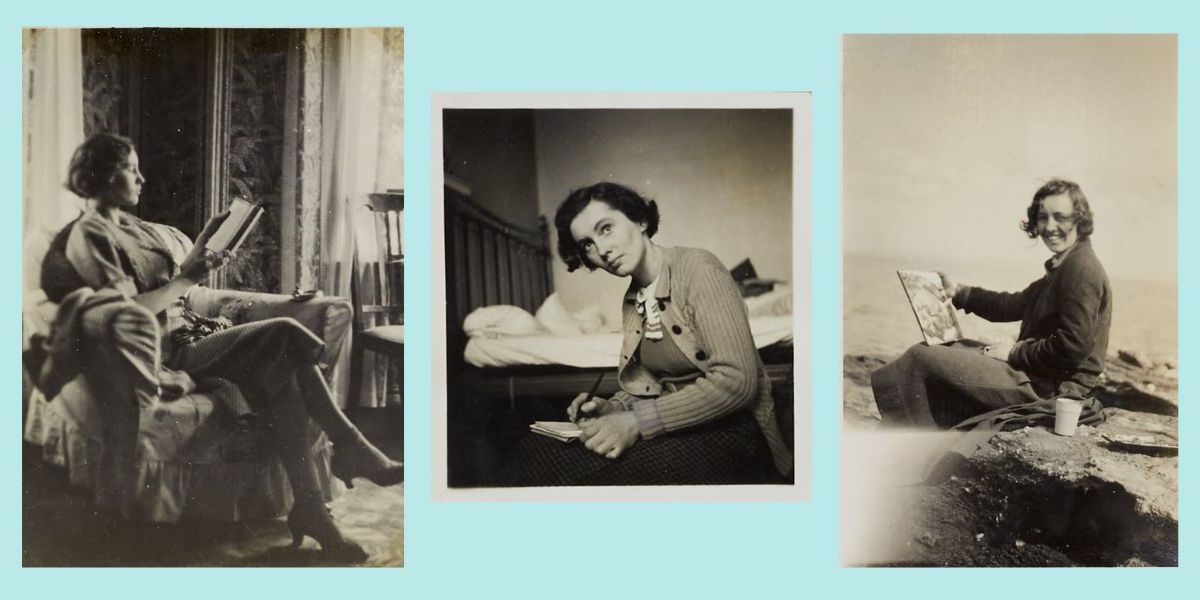

Three photographs of Barns-Graham as a student at ECA. Photographers unknown.

The Meaning of Art

The context in which Barns-Graham read the book is also important: she began studying at the Edinburgh College of Art in 1931, and in her second year she attended a course by Herbert Read called Modern German Art. Herbert Read was also professor of Fine Art at the University of Edinburgh from 1931 to 1933, where he gave lectures that were open to the art students on payment of a subscription. Read’s lectures covered aspects of historical European art and current developments in continental painting, sculpture and architecture. The course of lectures followed to some extent the format of his book The Meaning of Art, which Barns-Graham acquired in 1932 as a result of attending his lectures.

Beyond the academic world, the Society of Scottish Artists in Edinburgh organised exhibitions of modern and contemporary artists in the 1930s, thanks to the influence of the University’s professors. In 1931, for example, there was a major exhibition devoted to the Norwegian artist Munch, and in 1934, 25 works by Paul Klee were exhibited. As their mention in Green’s A Studio Life proves, these exhibitions were an important visual source for Barns-Graham and an important source of exploration for Herbert Read.

Read’s influence on the Edinburgh art world can be credited with contributing to Barns-Graham’s artistic development while she was a student. Herbert Read may also have played a part in the Barns-Graham’s sense of belonging to a Scottish art form during this period (Green, 2011). Indeed, in his inaugural lecture at the University of Edinburgh, Read was quick to appeal to local sensibilities and Scottish national pride when he envisaged his adopted city reaffirming its position in the late-Georgian intellectual world as well as arguing for the inclusion of contemporary art in the university’s curriculum (Green, 2011).

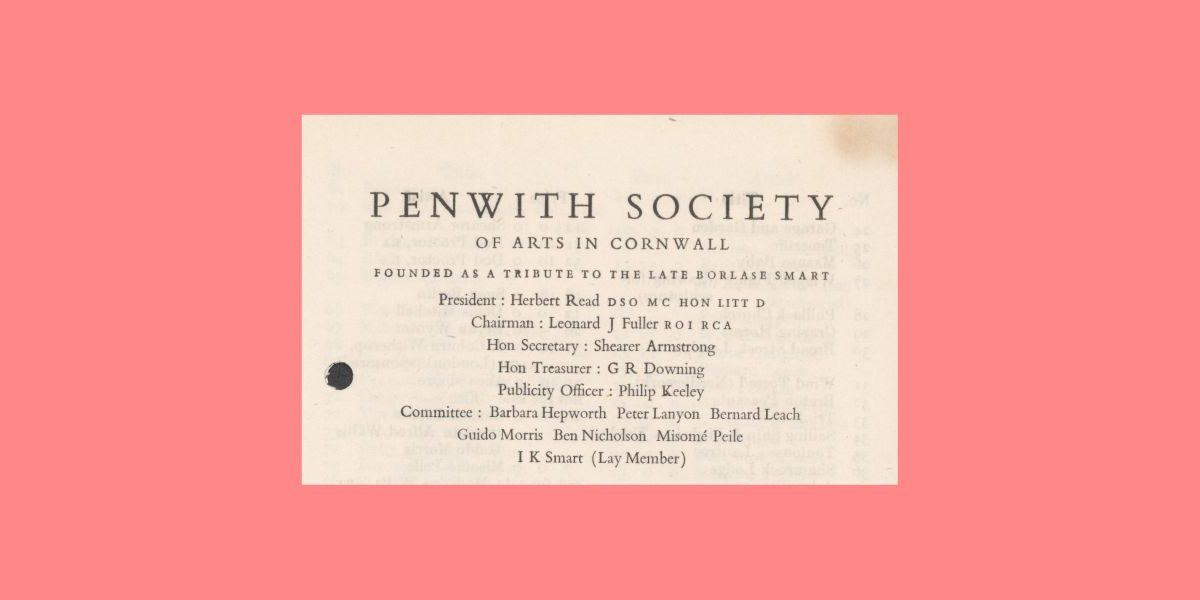

Extract from the catalogue for the First exhibition of the Penwith Society (WBG/3/9/1/1/1)

“I followed his writings, poetry and essays…”

Lynne Green also details how, as a young art student, Barns-Graham felt about her teacher: “[he was] a quiet, sensitive and gentle voiced man, pale face and wearing a dark suit. I found it difficult in those days to think of him as an anarchist. I followed his writings, poetry and essays and read The Green Child [published in 1935].”

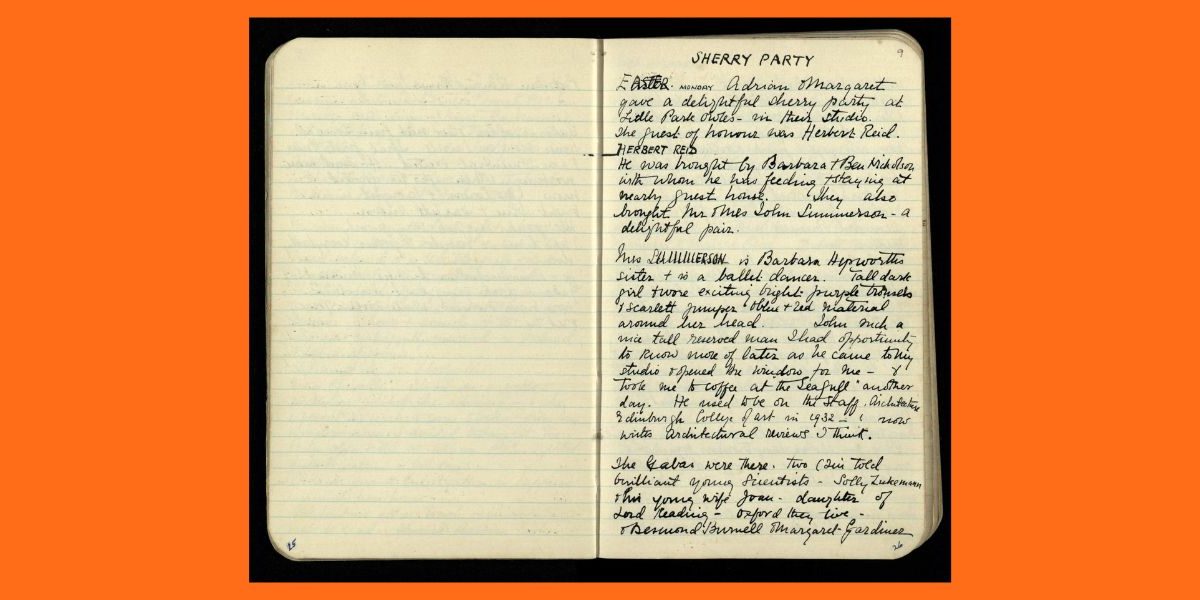

This description matches the one Barns-Graham gave in her diary a few years later when she found Herbert Read as the guest of honour at a Sherry Party given by Margaret (Mellis) and Adrian Stokes in St Ives. She recorded this event in her diary of 1940, in which she diligently noted all the people she met:

“I enjoyed the party immensely. Spoke mostly with the Buchanans, Adrian, Miriam + Herbert Reid. […] I know Herbert Reid wifes sister […]so that made conversation easy. He gave me a wonderful Mexican cigarette out of a yellow packet. The cigarette was black + strong. […] He is a charming person to talk to + awfully like mature Creiff Williamson same lethargic ease + manner. He’s gone much freer since I last saw him – at a lecture some years ago in Edinburgh when he was on Fine Arts dept. […]”

It was then that Barns-Graham met Herbert Read more closely through the artists she met with frequently in St Ives, and for whom Herbert Read was a spokesman.

'Sherry Party', extract from Barns-Graham's 1940-41 St Ives diary (WBG/4/1/5)

A frequent visitor

A frequent visitor to the St Ives group of artists – notably to Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Naum Gabo – Read became the first President of the Penwith Society of Arts, of which Barns-Graham was an active founding member in 1949.

Read explored and commented on the art of these artists, whose studios he frequently visited, and Barns-Graham was no exception. She is mentioned in Herbert Read’s book Contemporary British Artists (1951), several copies of which are in her library, where her name appears just after that of Francis Bacon:

‘WILHELMINA BARNS-GRAHAM. Born at St Andrews, 1912. Edinburgh College of Art, October, 1931-6. Awarded post-graduate travelling scholarship 1937. (Plate 52)’

Herbert Read’s writings combined with the theories of other St Ives artists, such as Naum Gabo, and contributed to the way Barns-Graham interpreted her surroundings.

Lynne Green described Barns-Graham’s process:

‘The Swiss glaciers offered the latter a perfect illustration of how internal forces determine external form, but all these artists understood and used dynamic to express both natural and psychological themes. […] Through assimilation and distillation (a process, as BG said, of laying the bare essentials), the given elements of line, volume, colour and light, together with the other dimensions of her experience (psychological, emotional and spiritual) began to re-emerge imaginatively and plastically. […] The process of abstraction was intuitive and spontaneous, the response dictated by the life of the individual work, not by the external world.’ (Green, 2011)

A selection of books by Herbert Read in the library of Barns-Graham and Rowan James.

A point of divergence

In 1959, in the ‘Great Britain’ section of Art Since 1945 which included essays by leading international historians and critics, writing on ‘the artists they regard as most important’, Read included Barns-Graham’s work in a category he called ‘metaphoric’ abstraction (the translation of experience into symbols). Read’s approach to Barns-Graham’s work seems to be tinged with a symbolist reading close to that of the Surrealists and centred on the symbols of the unconscious. Indeed, this intuitive work could bring Barns-Graham closer to a part of Surrealism, however, she never identified with the movement.

This was a point of divergence between Barns-Graham and Herbert Read, who was a fervent supporter of the Surrealists, having written extensively on Surrealism, and had organised the seminal Surrealist exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in London in 1936. As Lynne Green reports in A Studio Life:

‘Not always entirely resolved as finished works of art, these canvases reveal her investigation of the personal implications of Cubist ideas: she [Willie] told J.P. Holdin that she was ‘very interested in cubism [whereas] Surrealism doesn’t affect me; I have no affinity with it’ (Green, 2011)

But Read was not the first to attempt to categorise Barns-Graham’s work. Her work was included in Michel Seuphor’s 1956 Dictionnaire de la Peinture Abstraite and in Wilenski’s The Modern Movement in Art (1927) in its 1957 expanded version. ‘Wilenski discusses her art in the context of a group of painters that includes Gear, Victor Pasmore, Terry Frost and the Frenchman Pierre Soulages, who are concerned with what he calls an ‘empirical aesthetic’, which is essentially symbolic’ (Green, 2011). Wilenski’s discussion of the influence of the legacy of Cubism on the new generation of painters is also particularly relevant to Barns-Graham’s large series of glacier paintings, and rock forms that predominated her work in the 1950s.

Barns-Graham was clear that she was interested in cubism, not surrealism. Cubism is a translation of the perceived world that emphasises the flatness of the surface. The representation of the object or form as a series of interlocking elements on this flat plane is clear in Barns-Graham’s glacier series of artworks.

‘Through her reduction of ice or rock to a small number of separate but related shapes, movements and rhythms, Barns-Graham’s paintings become an abstract evocation of the multifaceted nature of three-dimensional form, and of the multiplicity of the visual reading of it: symbolic of what she describes as ‘the total experience’.’ (Green, 2011)

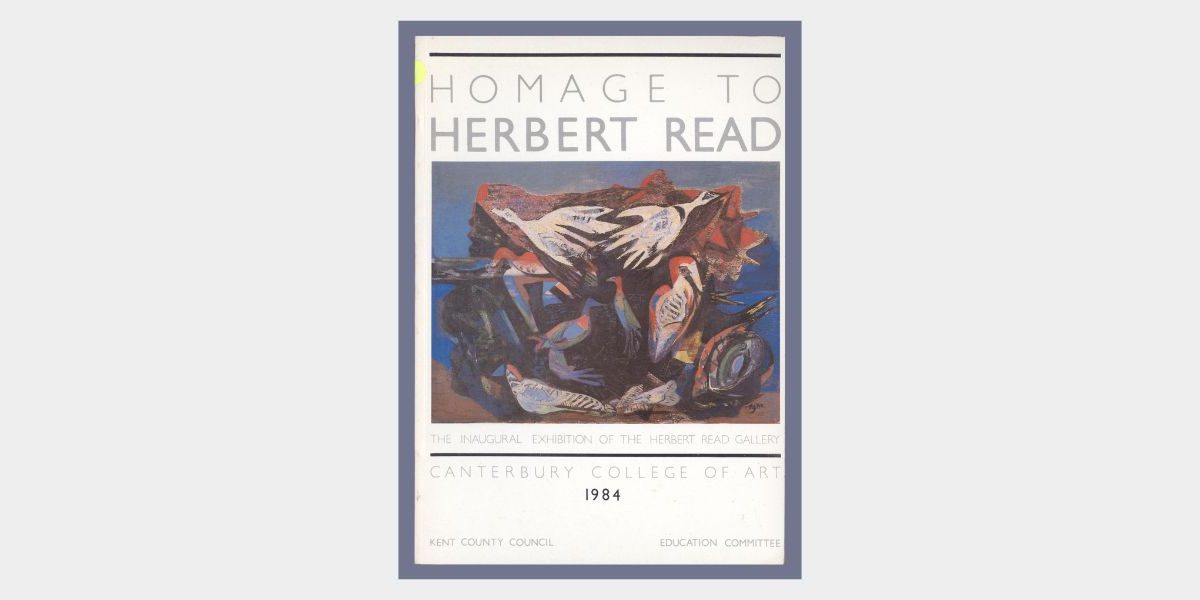

Catalogue for 'Homage to Herbert Read' exhibition at Canterbury College of Art, 1984

Close visions

In the end, Barns-Graham maintained a respect for Read’s scholarship throughout her long career. This is confirmed by an exhibition catalogue in the Barns-Graham library relating the exhibition Homage to Herbert Read in Canterbury, organised between 1 and 13 October 1984 to mark the opening of the new Herbert Read Gallery at Canterbury College of Art, named in honour of the poet and critic, where, she spoke about her own memories of him:

‘… Herbert Read was quick to spot a work at could impart generous enthusiasm. It was said in Edinburgh “Don’t expect him to give an immediate reaction to a work of art just seen, as he likes to go home and browse about it”; careful and particular, a man of few words but waited for and listened to. I particulary remeber him visiting my Barnaloft studio and I had a red gouache and her stopped on coming down the stairs, saying “What a good red I like that”… It was a major loss to art criticism when he died.’

The circle is complete, and Barns-Graham’s work can be summed up as follows: ‘Fiercely independent, Barns-Graham is a romantic at heart who believes that in the bewildering variety of life there is an underlying purpose – a principle, which manifests unity within apparent diversity.’ (Green, 2011)

The visions of Barns-Graham and Herbert Read were close. They understood the creation of beauty in the world in the same way but expressed it in painting for the former and in poetry for the latter. They saw harmony in the way the world shapes itself and believed in the existence of harmonious, universal physical laws that determine form (Read, 1931). Several natural forms possess the harmony and proportion that we usually ascribe only to works of art. In fact, effective form in the organic world, in the inorganic world and in the world of art is shown to be determined by identical laws. Beauty in art (as in nature) is the product of harmonious and balanced proportion, driven by the inspiration of the artist.

Bibliography

- Green, Lynne. W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life. New ed. Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2011.

- Homage to Herbert Read: A Catalogue for the Inaugural Exhibition [at] the Herbert Read Gallery, Canterbury College of Art. Canterbury, Kent County Council, Education Committee, 1984.

- King, James. The Last Modern: A Life of Herbert Read. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

- Read, Herbert. The Meaning of Art. Penguin Books, 1931.

- Thistlewood, David. Herbert Read: Formlessness and Form : An Introduction to His Aesthetics. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1984.

The WBGT would like to express our thanks to Margaux Beux-Pauly for the excellent work she completed while on placement with us between February and March 2025.