A Studio Visit: The Workplaces of Wilhelmina Barns-Graham

Amidst the current discussions about ‘working from home’ and ‘returning to work’ as coronavirus COVID-19 lockdown restrictions start to ease, Alice Strang takes a look at some of the studios Wilhelmina Barns-Graham used during her long and prolific career, sometimes at independent locations, at other times within her own house.

Studio Interior, Alva Street, c. 1935-37, Oil on canvas, 45.7 x 55.5 cm, BGT1056

During Wihelmina Barns-Graham’s fourth Academic Session at Edinburgh College of Art, of 1935-36, she took on a lease for her first studio in the Scottish capital beyond college premises. 5 Alva Street is a three-storey house in the west end of Edinburgh’s Georgian New Town. The basic amenities of Barns-Graham’s part of it are frankly depicted in her Studio Interior, Alva Street of the mid-1930s. An unlit fire, soot blackened brick fire-surround and unadorned walls are seen amidst loosely stacked canvases, brooms, an unfinished painting on an easel and a table and chair heaped with working materials. Her palette is based on low-toned browns and greys, enlivened only by the blue of the smock hanging over the edge of the open door and the cushion drooping off the chair. It is a no-frills, no-fuss depiction of a dedicated working space.

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham in her studio at 5 Alva Street, Edinburgh, November 1937

An Andrew Grant bursary of £10 along with a two-year Maintenance Scholarship from the college helped towards the rent and the studio symbolised her progression from undergraduate to post-graduate. Indeed, it was here that Barns-Graham prepared for her Drawing and Painting Diploma, which she was successfully awarded in 1937. Outwith the college, her exhibiting career began to develop during this period, through inclusion in group exhibitions staged by the Society of Scottish Artists (SSA) and the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA). A photograph of November 1937 shows a serious Barns-Graham in more organised and comfortable circumstances at Alva Street. With palette and brushes in her hands, she looks away from the accomplished painting, Edinburgh Interior, on her easel, every inch the emerging artist.

Not long after the outbreak of World War Two on 3 September 1939, Barns-Graham’s Special Maintenance Scholarship was renewed and. Hubert Wellington, the Director of Edinburgh College of Art, suggested she combine it with a Travelling Scholarship deferred due to earlier ill health and move to St Ives. A growing group of modern artists, including Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, had gathered around Barns-Graham’s college friend Margaret Mellis and her husband, the art critic Adrian Stokes. Wellington felt they and the Cornish climate would provide both professional and personal benefits for Barns-Graham. She arrived in St Ives on 16 March 1940 and was to retain a base there until the end of her life. However, she initially maintained her foothold in Edinburgh and kept up her Alva Street studio, sub-letting it to Denis Peploe and others, it is thought until 1941.

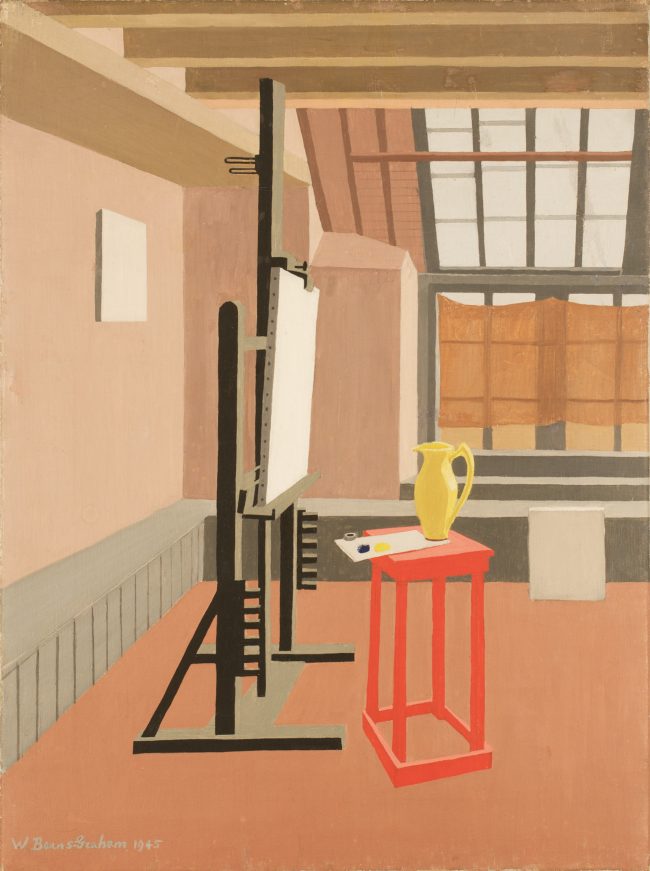

Studio Interior (Red Stool, Studio), 1945, Oil on canvas, 60 x 45.6 cm, BGT6408

Barns-Graham soon established herself as part of what has become known as the St Ives School. She joined exhibiting societies such as the Newlyn Society of Artists and St Ives Society of Artists, whilst continuing to send work to the SSA and RSA. During the war she worked in a camouflage net factory and served as an Air Raid Warden. In 1945, she moved from No. 3 to No. 1 Porthmeor Studios in the heart of St Ives, facing north over Porthmeor Beach. Barns-Graham continued to live in modest hotels or guest houses, whilst dividing her studio into working and domestic areas.

Studio Interior (Red Stool) of 1945 is a celebration of her new working environment. The composition has a very strong construction, provided by the horizontals and verticals of the low wainscoting, window frames, eaves, easel and stool. Three blank canvases adorn an otherwise empty room. One hangs on the wall, one is propped up beneath the windows, partly covered by material in order to mute the natural light entering through them and one ready on the easel. Bold colours are concentrated together, from the yellow jug to the palette prepared with two colours on which it stands, both placed on top of a bright red stool. The eye is therefore drawn to the subject of the painting: the potential to create, in this airy new space, in an image of unrestrained optimism.

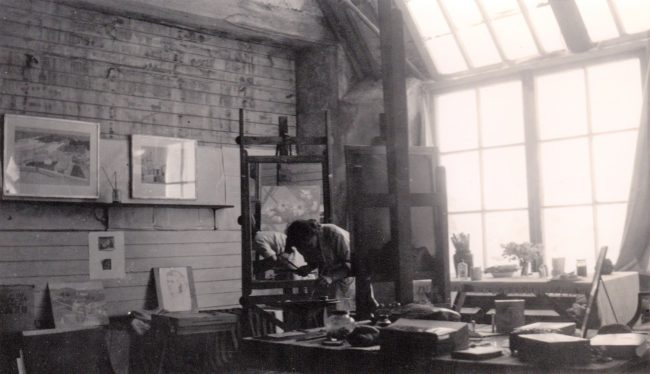

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham in No.3 Porthmeor Studios, St Ives, c.1945

A photograph taken not long afterwards shows Barns-Graham bending down between mirror and easel. It shows the same studio corner, but from a position to the right of that seen in the painting. The various works on shelves, the items placed along the window-sill and large table with a view of the sea, show how she had settled in to her surroundings and was leading a productive creative life there. She was to continue working in this space until the early 1960s.

Studio Interior 1947 II, 1947, Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 60.1 cm, BGT1256

Indeed, Barns-Graham celebrated No. 3 Porthmeor Studios in several paintings including Studio Interior II of 1947. Showing a different view, its complicated composition features layered screens, various items of furniture, a stack of canvases at the lower right and rugs on the floor. The bare walls and all-white elements contrast with the highly-patterned and coloured textiles covering the right-hand screen and draped over that on the left. A cropped poster for a Modern Scottish Painting exhibition is visible on the far left.

A Meeting of the Crypt Group in Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Porthmeor Studio, St Ives, 1947 Left to right: Peter Lanyon, Bryan Wynter (obscured), Sven Berlin, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, John Wells and Guido Morris

The adjoining view to the left was captured in a photograph in the ‘Art Colony, St Ives’ series taken by the Central Office of Information that year. Barns-Graham is seen standing amongst her seated Crypt Group colleagues, including Peter Lanyon and John Wells, captured in serious discussion. The group was named after the crypt in the St Ives Society of Artists’ New Gallery, the deconsecrated Mariners’ Church, where three exhibitions of work by advanced artists were installed between 1946 and 1948. This photograph reveals not only Barns-Graham’s position at the centre of the St Ives art world, but also her lonely place as one of the few woman artists within it.

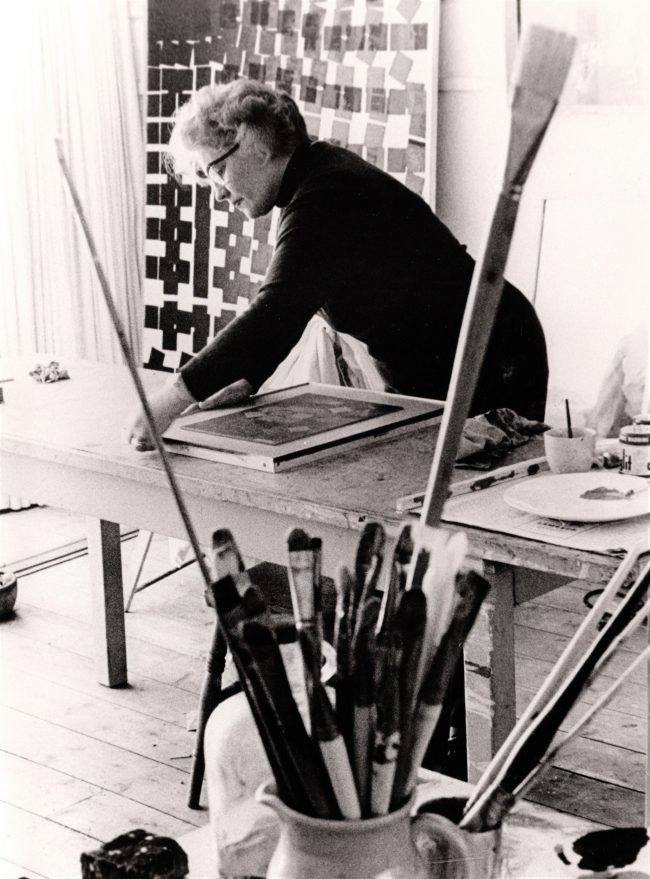

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham in her studio at No.1 Barnaloft, St Ives, 1966. Photo: Anders Gunn

Following a trip to the Grindelwald glaciers in Switzerland in 1949, Barns-Graham painted a major series of works with which she established her reputation as a pioneer of British abstraction. She pushed the boundaries of this genre through continual experimentation for the rest of her life. In 1960, Barns-Graham inherited the Balmungo estate outside St Andrews from her aunt, Mary Neish, who had supported her wish to attend art school; she thereafter straddled both the Scottish and English art worlds, dividing her time between Cornwall and Fife. Three years later, Barns-Graham purchased a ‘studio residence’, No. 1 Barnaloft, further along Porthmeor Beach, which proved to be her longest-standing and final studio in the south.

A photograph of 1966 shows Barns-Graham in Barnaloft, tending to the frame of a work and viewed through a jug of paintbrushes in the foreground. Behind her is a monumental Progression work of the mid-1960s. Lynne Green has explained that in these paintings ‘the squares were seen as ‘entities’, crowding each other, unifying with or separating from each other as individuals do. The orderly progression of squares is disturbed by displacement, or by a contrary movement, as in the ebb and flow of nature and in the dynamic of human interaction.’ Sustained commitment to her work, foreign travel and extensive exhibiting activities, whether in group or solo shows, saw her career flourish, although periods of ill-health, personal unhappiness and the vagaries of the art market saw her professional success waver at times.

Studio Interior, 1991, Oil on canvas, BGT1252

Studio Interior of the 1990s makes a sombre contrast to Studio Interior (Red Stool) of some fifty years earlier. Painted when Barns-Graham was in her eighties, it shows the view across the front working space at Barnaloft, out to the sea. This time an empty drawing board and chair look more neglected that awaiting use, whilst a canvas is turned away from sight, against the wall on the left. The slanting diagonals of the bare floorboards lead to the horizontals of the balcony, beach, sea, sky and blind. All colour is subdued, as apparently was the artist’s mood.

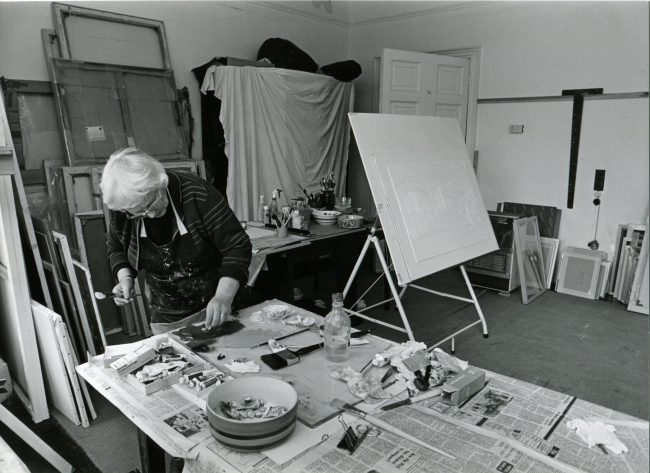

Wilhelmina Barns-Graham in her studio at Balmungo outside St Andrews, 1982. Photo: Antonia Reeve

Meanwhile, at Balmungo, Barns-Graham used her grandparents’ former drawing-room on the first floor as her studio. Situated at the front of the house, its bay window commanded fine views over the garden. A photograph of 1982 shows her busy working on the flat, on a newspaper-covered table on which a plethora of artist’s materials have been gathered. As in the Alva Street interior of the mid-1930s, no pretence is made that this is anything other than a utilitarian room, despite the hints of an earlier more genteel use provided by the hanging rail and panelled door. The ever-present stacks of canvases, some much larger than seen before, compete for space amidst the equipment involved in working on them. This time, the drawing board is occupied, standing at the centre of a place of activity.

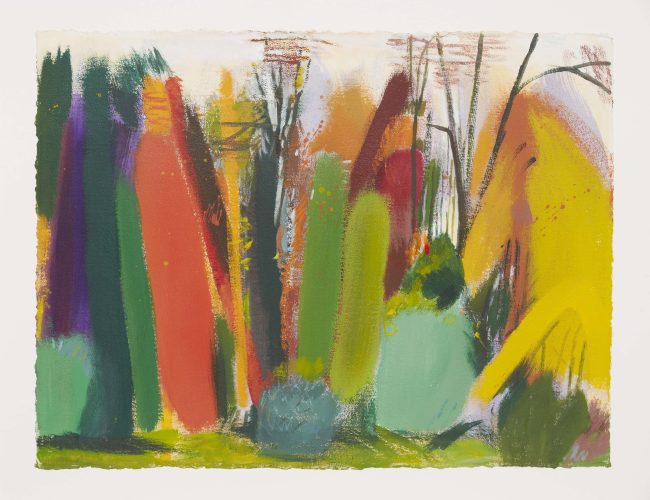

Autumn Series No.4 Balmungo, 1998, Acrylic on paper, 57.9 x 75.6 cm, BGT3019

Barns-Graham is not known to have depicted her studio at Balmungo. However, Autumn Series No. 4 Balmungo of 1998 is believed to be one of several works made in response to the view from it. It is a wonderfully vigorous image inspired by the specimen trees planted by her grandfather. Energetic mark-making is combined with sophisticated tonal relationships only achievable by a master of both abstraction and of colour. It dates from an extraordinary late burst of creativity with which Barns-Graham career of some sixty years concluded; she died at Balmungo in 2004.

All works and photographs are in the collection of the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

I am indebted to Lynne Green’s book W. Barns-Graham: A Studio Life (Lund Humphries, Farnham 2001 and second edition 2001) for much of the information contained in this article.

Alice Strang is an Art Historian and Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art. She is a former Trustee of the Wilhelmina Barns-Graham Trust.

Twitter @AliceStrang

Instagram @alice.strang

Website: https://alicestrang.co.uk/