Wilhelmina Barns-Graham: an artist at work

Throughout her career Barns-Graham was photographed in ways that identified her closely with the everyday minutiae of making art, and connectedly with the studio spaces staging these small yet vital and accumulative creative acts. Across the decades, the portraits of Barns-Graham absorbed before a canvas track her history as a painter. Barns-Graham trained and later worked at a time when it was still unusual for women to find much enduring or meaningful commercial success as artists, and this obscurity went particularly unopposed amongst the St Ives modernists, who like Barns-Graham settled in and around the town during and after the Second World War, most of whom were men. The large number of photographs dedicated to situating Barns-Graham within St Ives and laying claim to her identity as an artist there implicitly comments upon the anomalous status occupied by a woman in that circle, and mounts resistance to her possible exclusion. Photographs of male artists in their studios had long functioned within culture to naturalise ideas about who should and could become an artist, and it is difficult to convey just how radical it was for Barns-Graham to seize this mode of self-presentation for her own use.

Photographs in this display cover over 50 years of Barns-Graham’s long working life, from the 1940s to the 1990s, and subtly track the development of her aesthetic from a figurative to an abstract one. The photographs are also a study of three studios, and their accompanying frames of mind, habits and aesthetics: at Porthmeor, then Barnaloft in St Ives and in her Scottish home at Balmungo, Fife.

The images and text in this article were originally selected and written by Rebecca Birrell for an exhibition at Porthmeor Studios, on display from 11 September 2021. Rebecca’s first book This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century has just been published.

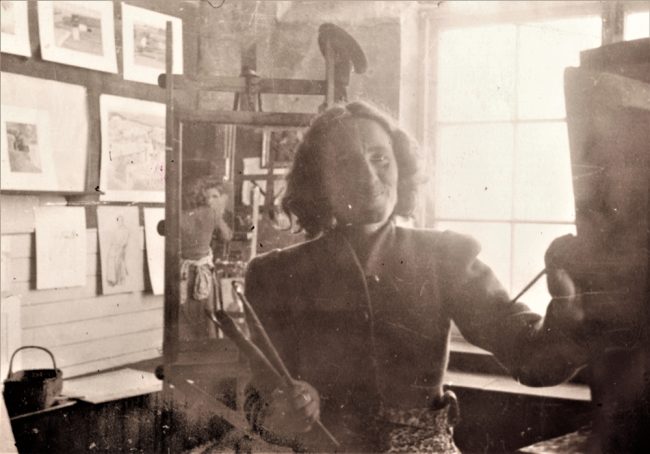

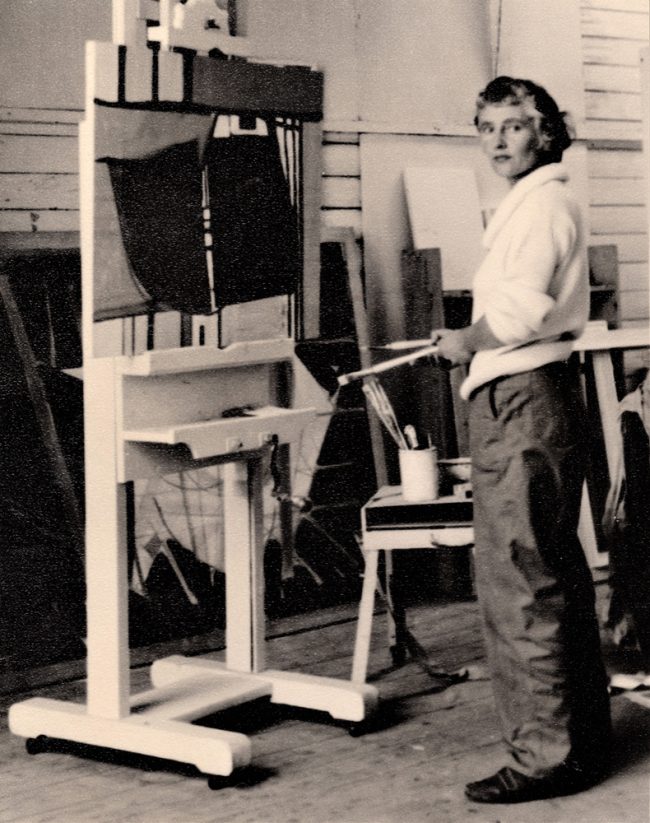

c.1941

Observed in what appears to be a private moment of artistic work, Barns-Graham loads her brush with paint, a still life canvas before her on the easel. Finding a studio in March 1940 marked an important moment in her career, signalling a dedication to her practice and to St Ives, a setting promising new subjects and challenges. The central location of the studio, its proximity to other artists and galleries, only compounded its seriousness as a statement of intent. Barns-Graham moved from No.3 Porthmeor Studios to the even bigger No.1 studio in 1946 and found it so fruitful for her work that she remained there until the early 1960s.

Update [03/03/22]: a new discovery in our archive dates this photo to c.1942 and names the person Barns-Graham is painting a portrait of as Per Hektoën, a Norweigian naval officer (just seen in mirror).

c.1941

Photographs of her studio reveal some of the strategies artists like Barns-Graham used to enhance or assist their process. Setting up a mirror behind her as she painted allowed Barns-Graham to see the canvas from a greater distance: certain colours and forms only revealed their wrongness within the composition when observed from this alternative perspective. This was a technique used by Renaissance draughtsman like Leonardo and was likely something she picked up during her studies at the Edinburgh College of Art. On arriving in St Ives, Barns-Graham’s diaries record the pleasure she took in painting portraits, a practice at once creative and social allowing her to network amongst other artists and make new friends.

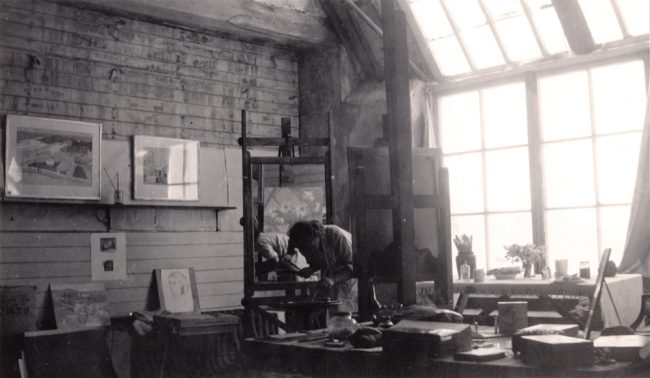

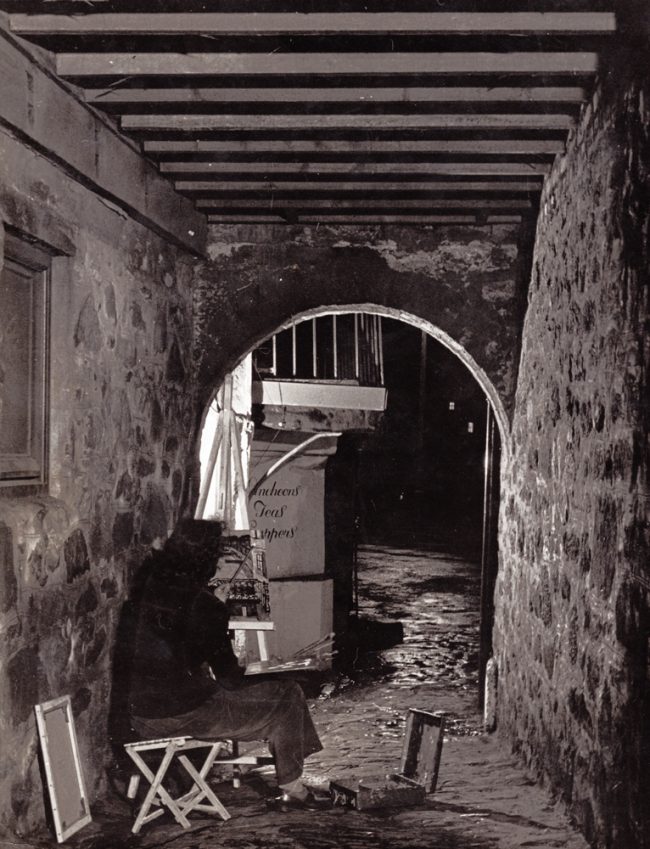

1947

Barns-Graham also found inspiration in the area immediately surrounding her studio, frequently taking her painting materials out onto the cobbled lanes of St Ives. Indeed, the painting seen in this photograph was one of a series using a single location on those streets as its subject – a set of ornate railings overlooking the harbour. Obviously staged (she is not looking at the view shown on the canvas on the her easel, nor would she likely be out painting at night), this photograph was published as part of a set titled ‘Art Colony: St Ives’ circulated by the Central Office of Information – a government communications body designed to inform the public on a vast range of contemporary issues in the United Kingdom.

1947

Barns-Graham stands before her painting Grey Sheds, St. Ives 2 (1947), a work showing her enduring interest in the architecture of St Ives. In common with other artists recovering from the uncertainty and destruction of the Second World War, Barns-Graham depicted the country’s landscape in a faithfully figurative idiom, contributing to a reserve of symbols fixated on aligning quintessentially British scenes with permanence, community, legacy and nationhood. This is another carefully staged composition – it is unlikely she would have still been actively painting a work already in an immaculate new white frame.

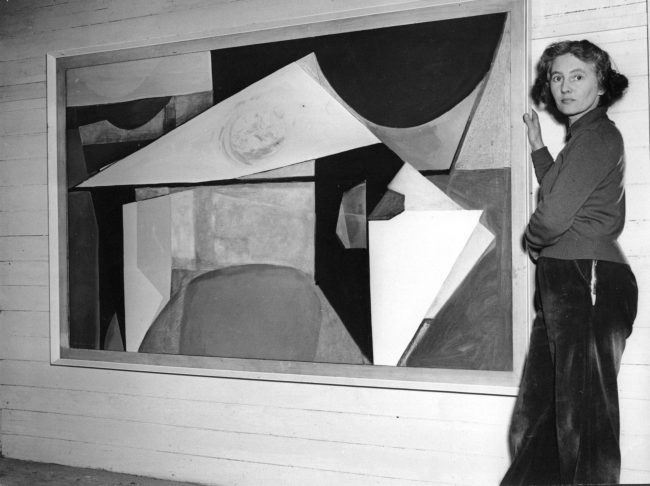

1954

The 1950s saw Barns-Graham definitively refocus her attention on abstraction, a movement met with excitement by artists in her circle, but some reticence on the British art market. Here she is photographed alongside Rock Forms, a particularly large painting for the period, which transforms the Cornish landscape into swooping lines, interlocking forms and opaque colours. For a time Barns-Graham was reluctant to show her abstract paintings even to friends; here, however, she asserts her connection to and presence alongside her experimental work.

1954

After years of mostly European influences, in the Fifties Barns-Graham was introduced to American art, artists, critics and dealers, and developed her aesthetic in dialogue with a number of avant-gardes, including abstract expressionism. This movement encouraged the artist to be self-reflexive about their medium and process, placing emphasis on the formal decisions and physical motions that went into a painting. On both sides of the Atlantic, photographs capturing preparatory work and technique placed further emphasis on the artist’s gestures. These images capture the moment paint is poured, splashed or laid across the canvas, or, in this instance, the preliminary stages in which the artist mixes her colours and loads her brush.

1954

During this decade, Barns-Graham repeatedly posed the question of what painting could do, what new rendering of the world was possible through applying the principles of abstraction, and did so through experiments with form, studying the surprising interactions between line, colour and affect. The painting pictured here is typical of her work in the mid-fifties, and is part of a series addressed to geological phenomena also including Rock Form (1954).

(photographed by Adrian Flowers (adrianflowersarchive.com))

Update [03/08/2022]: date was corrected from c.1955 to 1954. Photo was taken by Adrian Flowers in December 1954.

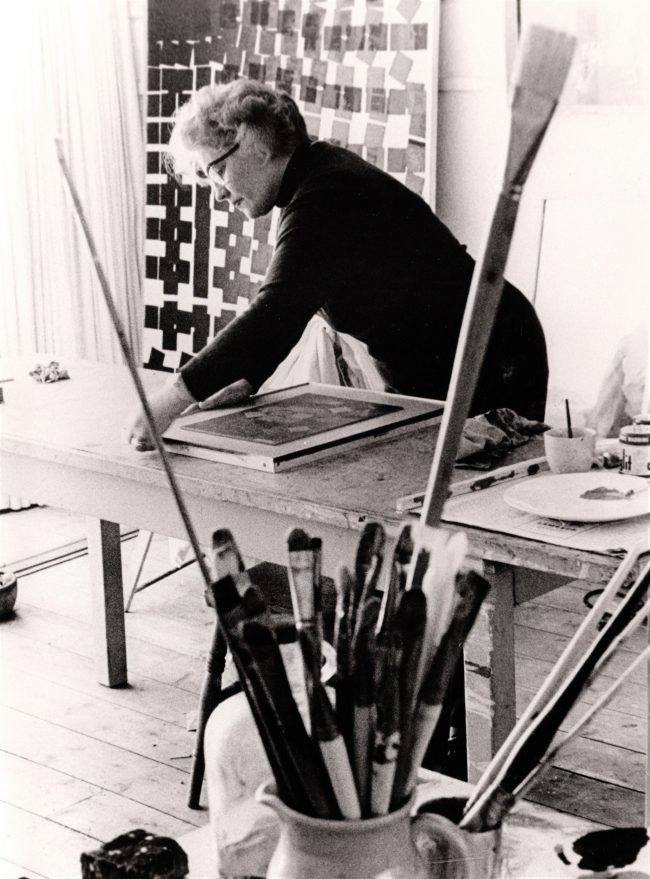

1957

The reverse of the original of this photograph reads: “before Wakefield exhibition”. The October 1957 show at Wakefield Art Gallery marked the culmination of an intense period of creativity for Barns-Graham. A number of paintings she completed that year (including those pictured here) explore the act of painting itself, emphasising control, deliberation and precision. On the studio wall is White, Black and Yellow (Composition February) 1957 now in the Tate collection (and currently on display at Tate St Ives). This was the artist as mathematician, rather than the vehicle of spontaneous creative expression. Across these canvases, Barns-Graham uses bold, jagged, angular forms to carve up the painted surface in geometric arrangements closely resembling one another, similarities suggesting a higher structuring principle: the Golden Section, an equation dividing and harmonizing elements of the canvas used by artists for centuries.

1962

Barns-Graham stands authoritatively before a canvas composed of bold interlocking shapes and horizontal lines relating to works made following time spent in Yorkshire at the end of the 1950s. This photograph was part of a set taken for a February 1962 article in the Cornish Magazine. In the interview, she evocatively summarises her art’s defining aims and principles. ‘I want my work to be a simple statement,’ she said, ‘To have an atmosphere and integrity – this is a presence… To have interesting space relationships, relationships of colour, and colour to form.’

c.1964

Amongst the photographs in Barns-Graham’s archive, whether at home or in the studio, there are dozens of images of cats. Here the companionship she found with animals is lovingly recorded, and in doing so the photograph also reveals the dual status of the studio: it was a living space as well as a professional one, where Barns-Graham could feel revived and connected both emotionally and artistically, a site of spontaneous intimacy and rigorous, careful making. In 1963, she purchased No.1. Barnaloft, a studio residence perfectly pairing these functions.

(photographed by Peter Kinnear)

c.1966

Barns-Graham stands next to Progression (1965), a major work now in the Leeds Art Gallery collection. In the sixties she became fascinated with repetition as a dynamic formal constraint. In an interview at the time, she observed how she had been ‘painting squares for six years now. I can’t stop… They have endless possibilities’. The immense potential she invested in that modest shape can be seen in this painting: here squares become a medium through which to explore elements of her artistic process, encompassing ideas about perception, description, tone, pattern, and balance, as well as broader social and emotional themes, such as presence and displacement, order and disorder.

1966

With Progression (1965) hanging in the background, Barns-Graham is at her drafting table framing a small work, which looks to be a similarly starkly geometric proposition. Assisting and inspiring these compositions were meticulous mathematical calculations, a technique which came to define Barns-Graham’s practice in this decade; yet these works were not without their own emotional charge. For it is possible to see within them the hours of errors and amendments, rigorous intellectual engagement and daring experiment, as well as the kind of care glimpsed here: making fastidious adjustments even to elements of presentation.

(photographed by Ander Gunn)

1975

Although the principles of experiment and rigour remained, in the 1970s, Barns-Graham began to engage with lighter, more playful themes, incorporating visions of birds and kites into otherwise austere formal arrangements. Barns-Graham remained committed to transforming her repertoire every decade, an invigorating self-consciousness which ensured her practice did not grow stale. The result of this new spirit were paintings distinct in their expressive, emotional qualities, at once capable of articulating private tragedies, atmospheric phenomena and an ongoing engagement with matters of form.

(photographed by Peter Kinnear)

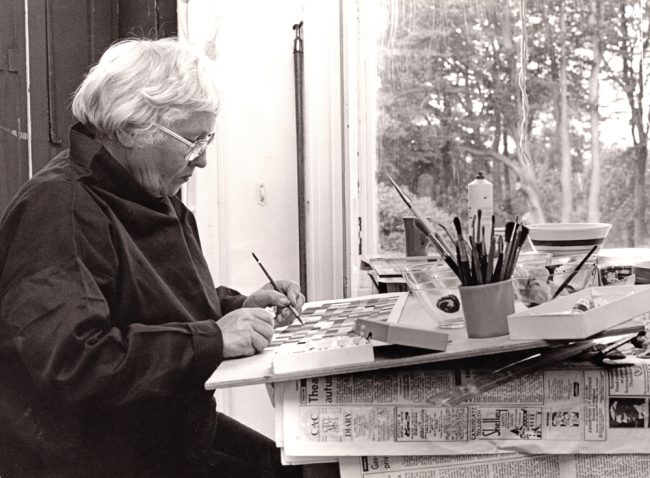

1982

Barns-Graham is pictured at work on an untitled painting, part of a series of small-scale abstract works emerging from her synaethesia. Many used a system matching colours to letters, transforming her palette into a cryptic alphabet, creating a text within the artwork often expressive of a spiritual message. In the eighties, Barns-Graham increasingly spent time at the home she inherited at Balmungo in Fife, and despite the meaning she had for decades invested in maintaining a studio in St Ives, found she could work comfortably and productively there too.

(photographed by Antonia Reeve)

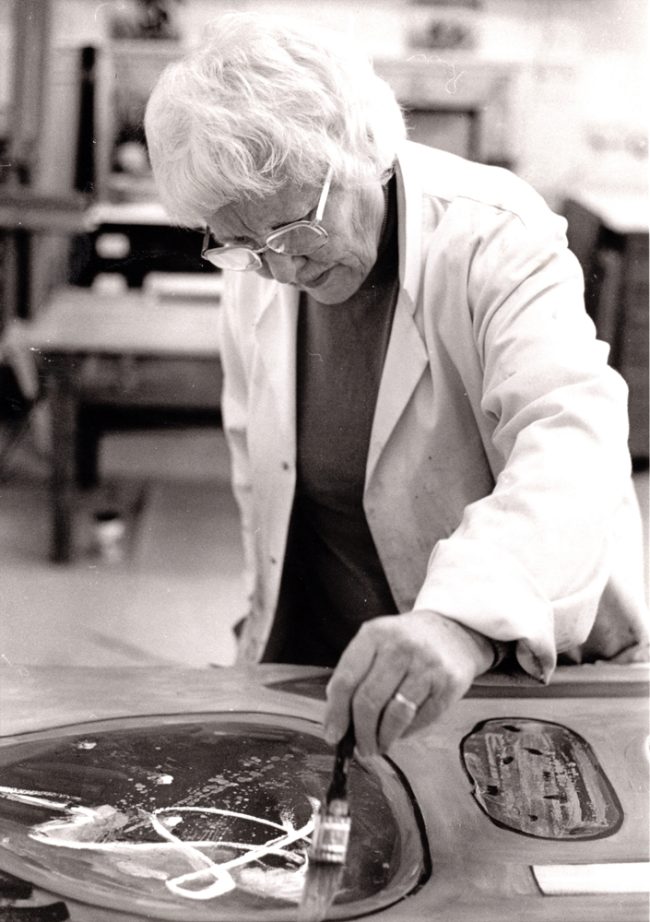

1986

Barns-Graham is observed working on Eight Lines, a spare and elegant compression of the Cornish landscape, equally evocative of sand dunes and the silhouette of waves in the ocean. In contrast, behind her is her 1985 Summer Painting No.2: this vibrant, playful piece uses the colourful towels and windbreakers, seen from her Barnaloft window on Porthmeor beach, as a resource for abstraction. Amongst her personal photographs, studies for this painting (which was part of an extensive series) show the visual pleasure Barns-Graham took in the raucous, ephemeral material culture of the beach just beyond her studio.

(photographed by David Crane)

1992

In the nineties, Barns-Graham dedicated herself to formulating fresh approaches to the most ineffable workings of nature, depicting elemental forces in highly original compositions striking in their mixture of loosely figurative and vigorously abstract idioms. In these works, gusts of wind might be conveyed in sweeping lines and sputtering marks, a directness balanced by the presence of enigmatic shapes resisting any neat classification, expressive merely of the land’s sturdy materiality or essential volatility. Partly this interest developed through Barns-Graham’s trips to Lanzarote, beginning in 1989, and her fascination with its unique landscape. Together with St Ives, Lanzarote became a touchstone for her in her later work.

(photographed by David Roche)